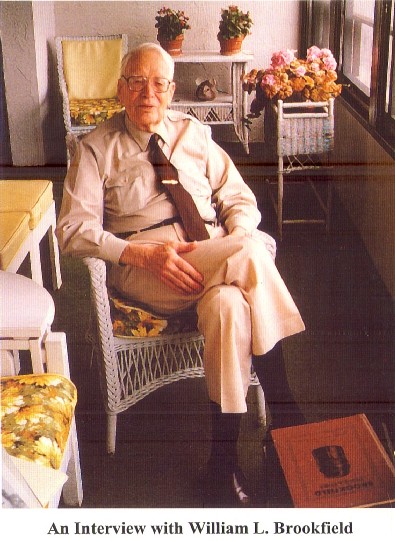

A Conversation with WILLIAM L. BROOKFIELD

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", December 1999, page 6

Recently Carol McDougald visited my wife Jean and me at our home in Shell

Point Village, Fort Myers, Florida. We had a long conversation about the

Brookfield Glass Company and this is the gist of what I told her, plus a bit

more.

Cover Photo

When I was a child my father would take me down with him to see the

Brookfield Glass plant. He had a broken glass dump that was enormous. A steam

shovel was used to move the glass around. Since I was the president's son the

men at the plant were nice to me. They taught me everything, let me work the

steam shovel and showed me how to make a barrel. At that time insulators were

packed in straw and shipped in barrels. The plant made its own barrels. I

remember the factory very well.

My great grandfather James Brookfield was a

glass blower. He was a frugal man and saved his money. He married a lady who was

fairly well off. He took his savings and some of his wife's money and in 1853

built a glass plant. It was successful from the start. After seven years, in

1860, the utility dam at Honesdale, Pennsylvania broke taking with it his

factory, his home, and all his possessions. He could not pay the interest on the

mortgage and had to go into bankruptcy.

|

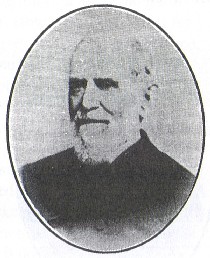

JAMES BROOKFIELD

1813-1892

James Brookfield was the founder of the original glass business at Honesdale,

P A. He obtained a patent on a furnace for burning hard coal and was the first

to use anthracite in glass-manufacturing. He started the Bushwick Glass Works in

Brooklyn, New York and obtained Patent No. 103,555 dated May 31, 1870 for his

invention of a screw machine to make glass insulators. He also helped his son

William Brookfield establish the Brookfield Glass Company. He retired in 1880.

|

About this time there was a brewer who

lived in Brooklyn by the name of Kalbfleish who made beer. The bottle makers

were charging him so much for his bottles that he could not make a decent

profit. He heard about the terrible catastrophe at Honesdale and contacted my

great grandfather, James Brookfield. He asked James and his son William if they

could build him a bottle plant and they said they could.

Mr. Kalbfleish agreed

to take a sufficient mortgage to pay for the plant and gave the Brookfields the common stock. He told them the

plant was theirs after the mortgage was paid. All he wanted was a sufficient

supply of bottles at a decent price. He said the Brookfields could make

additional products if they wished. After two or three years the mortgage was

paid and the plant belonged to the Brookfields. My grandfather was so pleased

that he named one of his sons Herbert Kalbfleish Brookfield.

One day when my great grandfather and grandfather were out to lunch, the

clerk was left in charge of the office. When they came back the clerk told them

a crazy man had tried to sell him a patent to put a thread in an insulator. My

grandfather said he would like to talk to the man but the clerk didn't know

where he lived. My grandfather told him to find the man or he would be fired.

|

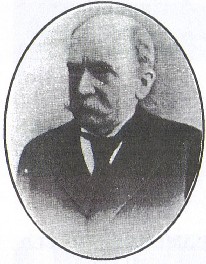

WILLIAM BROOKFIELD

1844-1903

William Brookfield was the founder of the Brookfield Glass Company in

Brooklyn, New York. He was the inventor of a new and better way of making

telegraph insulators by Patent No. 113,393 dated April 4, 1871. He was a

director of a New York bank and several insurance companies. He also was a

commissioner of public works in the city of New York and a presidential elector

in 1892.

|

After a couple of weeks, they located him. His name was Cauvet. He had visited

the other glass makers but none were interested. The reason nobody would buy was

because insulators at that time were stamped out like ashtrays and there was no

profit in making them. Money was made out of bottles, window glass, objects of

art, etc. My grandfather bought the patent. James Brookfield made a machine to put a thread in an insulator,

my grandfather made a faster one and my father made one that was automatic which

operated day and night. The man who sold him the patent was given a lifetime

income. However, he couldn't stand prosperity and after a couple of years he

died so the patent did not cost very much.

After the Cauvet patent was

purchased, the manufacturing of insulators became an engineering job so a lot of

the glass companies did not want to touch it. However, the demand for insulators

kept growing; first the telegraph, then the telephone, and then the power needs.

Everyone began to want the patent. The Brookfield Glass Company couldn't keep up

with the demand so they farmed out the business on a royalty basis which gave

them enough money to always keep ahead of the game with new improvements.

Before

threaded insulators, this is the way insulators were installed. Wooden pins were

placed on a cross arm of a pole. A man would come along with a bucket of water

and some newspapers. He would soak a gob of newspapers in the water, stick it

over the wooden pin, and hammer it down with a mallet. In the summer, everything

was fine - the lines would sag, but in the winter they would shrink and the

insulators would pop off. Also, objects might fall on the lines and off would go

the insulators. The result was there had to be linesmen walking the lines all

the time putting the insulators back. Thereafter the thread became very

important.

The company my great grandfather and grandfather started was called

the Bushwick Glass Manufacturing Company, sometimes referred to as the Bushwick

Glassworks. Besides bottles they made insulators for quite a while. After the

mortgage was paid off and the Brookfields owned the plant, the Bushwick Glass

Manufacturing Company was gradually dropped and the Brookfield Glass Company

name substituted.

The bottle blower's union kept giving Dad more and more trouble so finally he decided to move the plant to Old Bridge, New Jersey,

giving up making bottles and increasing the capacity for insulators.

I knew the

plant, I knew the employees, and, of course, I talked with my father. He told me

a number of stories about the plant.

One day he received an order for 100

barrels of insulators to go to a company in Puerto Rico - that's a good order.

The barrels were to be marked one to a hundred (1 - 100). They wanted them shipped

in two weeks' time. A week later he received another order from the same company

for another 100 barrels but they wanted them shipped on the same boat as the

first 100. The second batch was to be marked one hundred and one up (101 - up).

That was a very short time but Dad insisted that the factory produce them and

get them to the same boat in Jersey City.

|

HENRY MORGAN BROOKFIELD 1871-1960

Henry Morgan Brookfield was president of the Brookfield Glass Company until

it closed in 1922. Inventions to his credit include Patent No. 596,651 and

Patent No. 596,652 for a new press to make two or more insulators ( or other

glass objects) at a time, issued to him January 4, 1898, and Patent No. 646,948

and Patent No. 646,949 for his invention of a revolving press which enabled

insulators to be made continuously, issued to him on April 10, 1900, as well as

Patent No. 835,235 and Patent No. 835,236 issued November 6, 1906, which made

additional improvements on glass presses.

|

My father used to go to the office

fairly early but the chief clerk was usually ahead of him. The boat was to leave

Thursday morning on the tide.

On Wednesday morning the clerk said to him, "Do you know what that

blankity-blank plant has done?"

Dad said, "No, what?"

"They've marked that second batch 101 up. I was just checking to see if the

barrels had arrived at Jersey City pier."

Father said, "That's okay,

that's what I told them to do."

The clerk said, "You don't understand.

Each individual barrel is marked '101-up'."

So father, Uncle Frank, and a

painter all went down to the dock and marked the barrels properly. They were

loaded on time to make the boat.

My father was the President of the Brookfield

Glass Co. He was a Harvard graduate with a degree in chemistry. He took charge

of the plant and its production although his office was in New York. My Uncle

Frank Brookfield was the sales manager and, between them, they did very well. However, the war came along and Uncle Frank wanted to go to war. So

father, as his war effort, said he would handle both jobs. Well, it was awfully

hard work and some dreadful things happened.

First, saboteurs [My father told my

they were German agents. That's all I know.] set fire to the railroad yard, the

packing plant, and a whole train load of insulators waiting for an engine to

pull them out. They were ready to go to the allies (this was, of course, WWI).

The plant was rebuilt right away but it was costly.

Second, the Morgan Shell

plant blew up and shells from it landed in the vicinity. Practically every

window in the factory was smashed and the concussion of the shells knocked

things about.

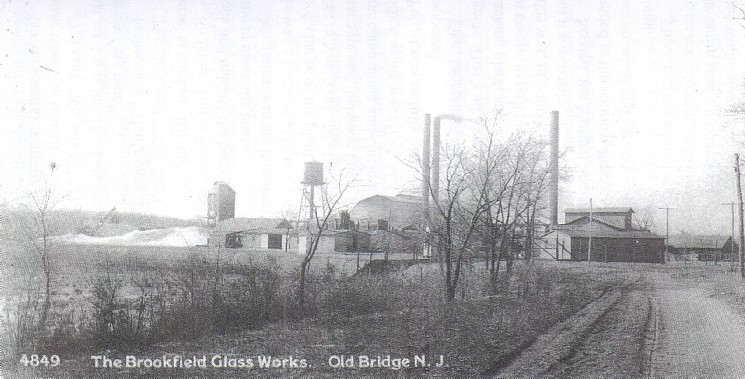

Postcard photograph of The Brookfield Glass Works in Old Bridge, New Jersey,

courtesy of David S. Sztramski. (See CJ, January 1996 "New" stuff from

"Old" Bridge.)

Note crane and bucket moving white sand to left of the

buildings.

Third, it takes a lot of coal to make insulators. There was no air

conditioning in those days so they would have to make the entire year's

production between October and June. Then they would shut the furnaces down

because it was too hot for the men to work. During the summer, the company would be selling. Coal was in

short supply and Dad was not on the preferred list. He had to shut the plant

down in January instead of June because he had no more coal. However, there was

such a demand for insulators abroad where they were fighting that Dad finally

made the preferred list but by that time the plant could only run a month or so

and I don't think they started until the next fall. At any rate, they lost

nearly one-half year of production.

The factory started up again and began to

make a profit. Then Uncle Frank came back from the war and didn't want to work

anymore. Unfortunately, my grandmother had died and left him some money.

Although my father received an equal portion, it was not enough to buy Uncle

Frank out.

So father had to find another partner. My Dad owned 51 % of the stock

and Uncle Frank 49%. Dad found a wonderful man named Wilson Fitch Smith, an

engineer, who had built the huge Valhalla dam for the water supply system of New

York City, and he was willing to buy the 49% ownership. However, he got

pneumonia and died just as the deal was being completed.

Father had been

carrying the whole business while Uncle Frank was away and, with all these

troubles, was able to keep the business going, but it was too much for him. I

was only 14 or 15 at the time. Dad said if I had been four or five years older

he would have tried to obtain a loan to keep the plant going. In 1922 the plant

was sold.

The buyer was a refrigerator company. The glass company owned a dock

on the Raritan River where barges could bring in steel and all kinds of things

necessary to build refrigerators and there was a railroad siding as well so it

was a pretty good place for a plant. Father never sold the patents or copyrights

because he'd always thought he would go into business again but that never

happened. The reason the Brookfield's sales went so well is because many of the buyers had engineering departments who thought that they could

make a more efficient insulator by changing its shape. Both my grandfather and

Dad catered to those people and custom made insulators for them. After the turn

of the century the plant employed about 600 men. A lot of things were done by

hand in those days when they did not have much automatic machinery.

Dad made

the glass insulators for F.M. Locke Co. They were going into the porcelain

business and asked father if he would make a porcelain insulators for him. So

Dad added a larger new wing to the plant for this purpose. A small porcelain

insulator could carry 10,000 volts with ease whereas it would take a big heavy

piece of glass to arrive at the same insulating ability.

I saw the new plant

with the porcelain furnaces, and I talked with the superintendent. He told Dad

he had run through several batches of porcelain insulators on a test basis and

everything worked well. This was around 1920 or 1921. I don't know what, if any,

marking was on these insulators but if you ever find one with

"Brookfield" or "B" on it, it could be worth a fortune.

Returning to the glass business, AT&T had a subsidiary named the Western

Electric Company which was the purchasing and engineering ann. Little by little

they kept buying more and more of father's insulators. They finally arrived at a

point where they were purchasing 50% of the Brookfield Glass Co. production. All

went well until there was a new purchasing agent who really tried to put the

screws on father.

Each year when he went to see the purchasing agent he'd come

back and practically have to go to bed for a week because he didn't know how he

was going to make a profit. He had to make it on the other 50% of his business.

Also that same agent gave him even more trouble. One of Dad's competitors came

out with a clear glass insulator. Father's were all aqua or green. The agent

told Dad those clear insulators were much better so Dad invited him to visit the Brookfield

plant. Father took a number of green glass insulators and put them in a line.

Then he placed the same number of clear glass ones also in a line. He put live

steam on both sets. Most of the clear glass insulators cracked but not a single

one of the green glass ones. He got the order.

I was brought up on the

Brookfield Glass Co. Every time Dad made a new insulator he would give me one.

However, they were so common that I never thought much about them. When I went

to boarding school my insulators were all thrown out. Mother just thought they

were dust catchers. A few people used to collect them but I thought they were

nuts - like collectors of matchboxes or beer cans.

Some years later our friend

"Woody" Woodward came up to see me. By this time father had died. He

came all the way from Texas to talk to me about insulators and the Brookfield

Glass Co. He spent a couple of days with me and I thought, gee, maybe I should

begin collecting these things. Woody gave me several to start. Then some other

people gave me some and I'm finding I have a pretty good collection now. I once

had over 500 but now I limit myself to 200 - all different, but all Brookfields.

Part of William Brookfield's insulator collection.

Each is labeled with the code name used by the Brookfield catalogues. Left

to right: Brookfield No. 54 Transposition Insulator "Dropa" (CD 196);

three No.3 Knobs "Flail" (CD 1104); No.5 Knob "Flame" (CD

1095); NO.7 Knob "Float" (CD 1087.1); CD 226.3; Brookfield No. 74

Circuit Break Insulator "Gater" (CD 1140); Brookfield No, 416 Circuit

Break Insulator "Gunda" (CD 1138); Brookfield No. 53 Transposition

Insulator "Drift" (CD 205)

You asked me if I had any old papers about the glass business. I have the

bankruptcy papers but I think possibly they should be destroyed. James had a

rough time when his plant was demolished. My grandfather, William, was on his

way to Yale University when he was called back to go to work. James had six

daughters who took in sewing, washing, dressmaking, cooking and everything to

try to keep the family afloat but no way could they pay the interest on the

plant mortgage. They did all this for a couple of years until Kalbfleish came

along. He gave James some money to keep him going until his plant was finished.

He was a wonderful man.

My uncle, George Debevoise, was in the paint business,

President of the Debevoise Paint Co. He wanted a plant in Brooklyn so my father

sold him the Brookfield Glass Co. property when he moved to Old Bridge, New

Jersey. A survey of the Brooklyn property was made and it was found that the

next door neighbor's property line was only a few inches over into Dad's

building. That created a problem. However, Uncle George was a super salesman and

he straightened out the matter. I think Dad had to pay something but it was not

much.

My father had a huge dump of broken glass, probably 25 feet high and a

block long. A lot of people who wanted jobs lived in the neighborhood. He used

to give each one a gunny sack and they would pick up all the broken glass they

could find. At the end of the day they would dump the sack on the pile and

receive a silver dollar for each sack. The broken glass was recycled.

In

discussing the colors of insulators if, in the manufacturing, there were

imperfections like swirls, big bubbles, streaks, etc., the Brookfield Co. rated

them as "seconds". Some they would throw out and others were sent to

South America, Canada and so forth at lower prices. The reason some Brookfields

are aqua and others green is as follows: when the plant was in Brooklyn most of the insulators were

made of Long Island sands which produced an aqua color. When the plant moved to

Old Bridge, the Jersey sands produced a green color. Also at Old Bridge a lot

of cullet was used which made an even darker green.

One day a man came to

father's office to show him some beautiful samples of fine white sand which came

from Florida. They were so good that Dad took out his pencil and figured that it

would probably cost too much to ship the sand to New Jersey but he was tempted.

He asked if there was a lot of that sand available. The salesman said there was

an unlimited amount. The place from which it came was Palm Beach before all

those buildings were erected down there. Dad could have bought most of the place

for practically nothing.

You asked me if Dad sold some peculiar looking

insulators (CD 640 "gingerbread boys") to France because some were

found in the Brookfield dump. I know Dad did sell some insulators to France but

I don't know of any with arms other than the O'Brien which was sold in Peru.

However, it is possible.

If you look in Milholland's Bicentennial Edition you

will find on page 32 a way to tell the age of most of the Brookfield insulators.

Many of them in the early days were marked Wm. or W. Brookfield. When my

grandfather died in 1903 the Wm. and W. markings were removed from the

insulators. During the 1st World War it was hard to find skilled people to make

the molds and, as the company was well known, the letter "B" was used

and sometimes nothing at all. It may not be true but I think a number of

insulators marked with ampersands (&), stars, etc may have been made

by the Brookfield Glass Co. but I can't prove it. The only thing is that a lot

of the shapes of the insulators conform exactly to father's.

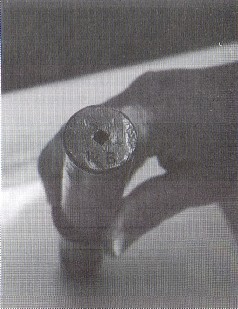

Family treasures include:

A china coffee set which belonged to Mrs. James Brookfield,

great grandmother

of William L. Brookfield.

A brass insulator pin (duplicate of pin at Bureau of Standards)

marked on end

with "WB" (William Brookfield).

The standard pitch for pin and pinhole threading is four threads per inch,

and the diameter for the Standard Pinhole is one (1") inch. This is the

extreme diameter at the top of the pin and at the bottom of the pinhole. The

standard taper for pin and pinhole is one-sixteenth (1/16") inch increase

in diameter per one (1") inch in length. It is important that all pins be

in accordance with standard specifications.

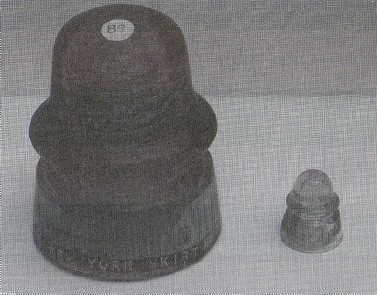

Brookfield miniature salesmen samples.

William Brookfield remembers his

father bringing home the small glass samples. Above is the miniature CD 162

style and its full-size counterpart signal. Below is the extremely rare beehive

style next to its Brookfield production clone.

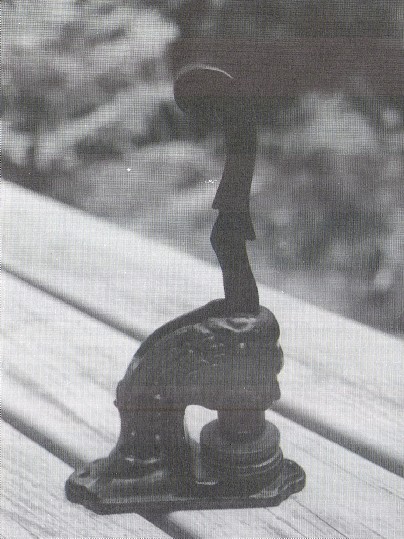

The company seal which embossed:

THE BROOKFIELD GLASS COMPANY

INCORPORATED

- · -

1908

- NEW JERSEY -

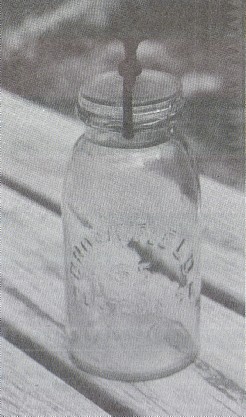

Rare Brookfield Jar marked:

BROOKFIELD

55

FULTON ST

N.Y.

The Brookfield canning jar, according to insulator and fruit jar collectors,

Tom and Alice Moulton, is probably one of no more than six known to exist. The

jar is cylindrical, aquamarine, applied collar mouth with a glass lid and an

iron yoke clamp (thumb screw) and has a smooth base. Most of the clamps

considered correct have a six pointed top but the standard eagle non pointed

clamp works. The eagle lid was considered to be the correct lid at one time but

Alice Moulton's jar has a much different unmarked lid. To our knowledge there is

no patent data on record and it is listed as being manufactured from 1860-1880

but that is sketchy at best. It certainly would have to be during the time frame

of 55 Fulton Street. Dick Roller's book, The Standard Fruit Jar Reference, says

"that it was manufactured by the Bushwick Glass works with the 55 Fulton

Street address - 1860's to 1882 (Proprietor William Brookfield). He (Roller) had

some documentation that stated that Bushwick was manufacturing Mason Jars in

1869 that were chipped and ground by the workers."

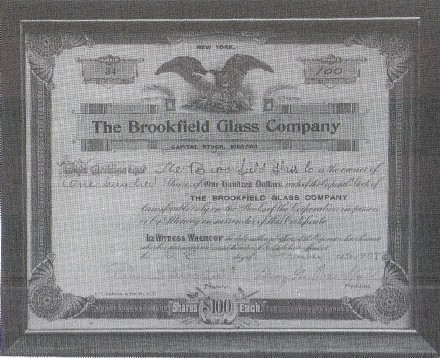

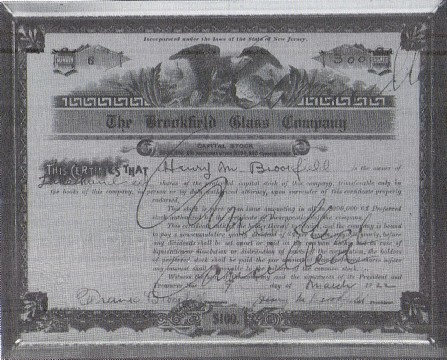

Two framed Brookfield Glass Company shares for common stock. The first was

issued to the Brookfield Glass Company for 100 shares at $100 each, dated the

28th of December. 1908 and signed by Frank Brookfield, Treasurer and Henry M.

Brookfield, President. The second certificate was issued to Henry M. Brookfield

for 300 shares at $100 each and dated the 9th of March, 1922, signed by Frank

Brookfield, Treasurer and Henry M. Brookfield, President. The word

"Cancelled" was handwritten twice across the face of the certificate.

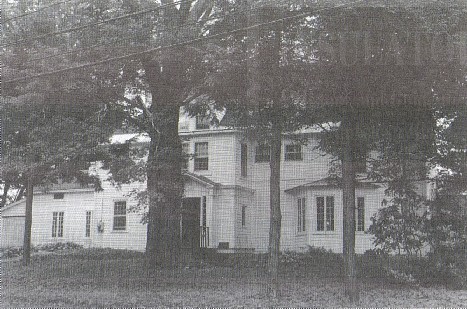

The home of Henry Morgan Brookfield

The beautiful white clapboard colonial so typical of New England is nestled

among a stand of large maple trees along the main road leading into the town of

Norfolk, Connecticut. Although no longer owned by the Brookfield family, it

elicits fond memories by William Brookfield as he travels by his childhood home

during summers spent at the lakeside family camps in the surrounding area.

I am indebted to Dave Sztramski, Cranford, New Jersey for his continued

interest in the Brookfield manufacturing company. He inspired me to do what I

have always longed to do -- interview William "Brooks" Brookfield. Our

Florida conversations were taped recorded and then transcribed by Candy Martino

so that Mr. Brookfield could make corrections and additions.

In the summer of

1998, John and I spent two days with the Brookfields at their Connecticut home.

Brooks (as William is affectionately known). and his lovely wife Jean are two of

the most gracious people one could ever meet. The calm of the lake, the

stillness of the woods, the darkness of the night, the aroma of a home-cooked

salmon dinner are memories permanently etched in our treasured hobby moments.

May God grant you both continued vim, vigor and vitality in the years ahead.

Thank you, Brooks and Jean.

Your Editor

The William Brookfields at home.

William Brookfield is a graduate of St. Paul's School and Harvard University.

He served on General Omar Bradley's staff in WW II and as a Lt. Colonel under

General Patton. He retired as an officer of the New Jersey Zinc Company in 1968.

|